#JUICELog: Escaping Earth

Europe’s first mission to the Jovian system has now left Earth behind, embarking on its eight-year journey to explore Jupiter and its vast ocean worlds.

Even now, I have to pinch myself writing those words. It’s not easy to articulate the highs and lows of the last 48 hours, but for me it was an unforgettable moment - heart-stopping, nerve-shedding, and ultimately filled with moments of dread and joy.

Thursday April 13th

I travelled to Darmstadt in Germany the night before the launch, for a sleepless night in a hotel near Europe’s Space Operations Centre (ESOC). Text messages flew between team members, as people tried to piece together scant information - when were the decision points for the go/no-go on a launch on April 13th? When would we know the launch had been successful? What was the weather like? All was whispers and hearsay, between those who made the trip to Kourou in French Guiana, and those of us at Mission Control.

The atmosphere at ESOC on the morning of April 13th was electric. A blend of old friends and colleagues, alongside social media influencers, the press, VIPs from ESA and the political world, all there for ESA’s moment on the world stage. The stage manager and presentation team herding us cats into position in the auditorium, where I was supposed to be speaking on the live ESA stream shortly after launch.

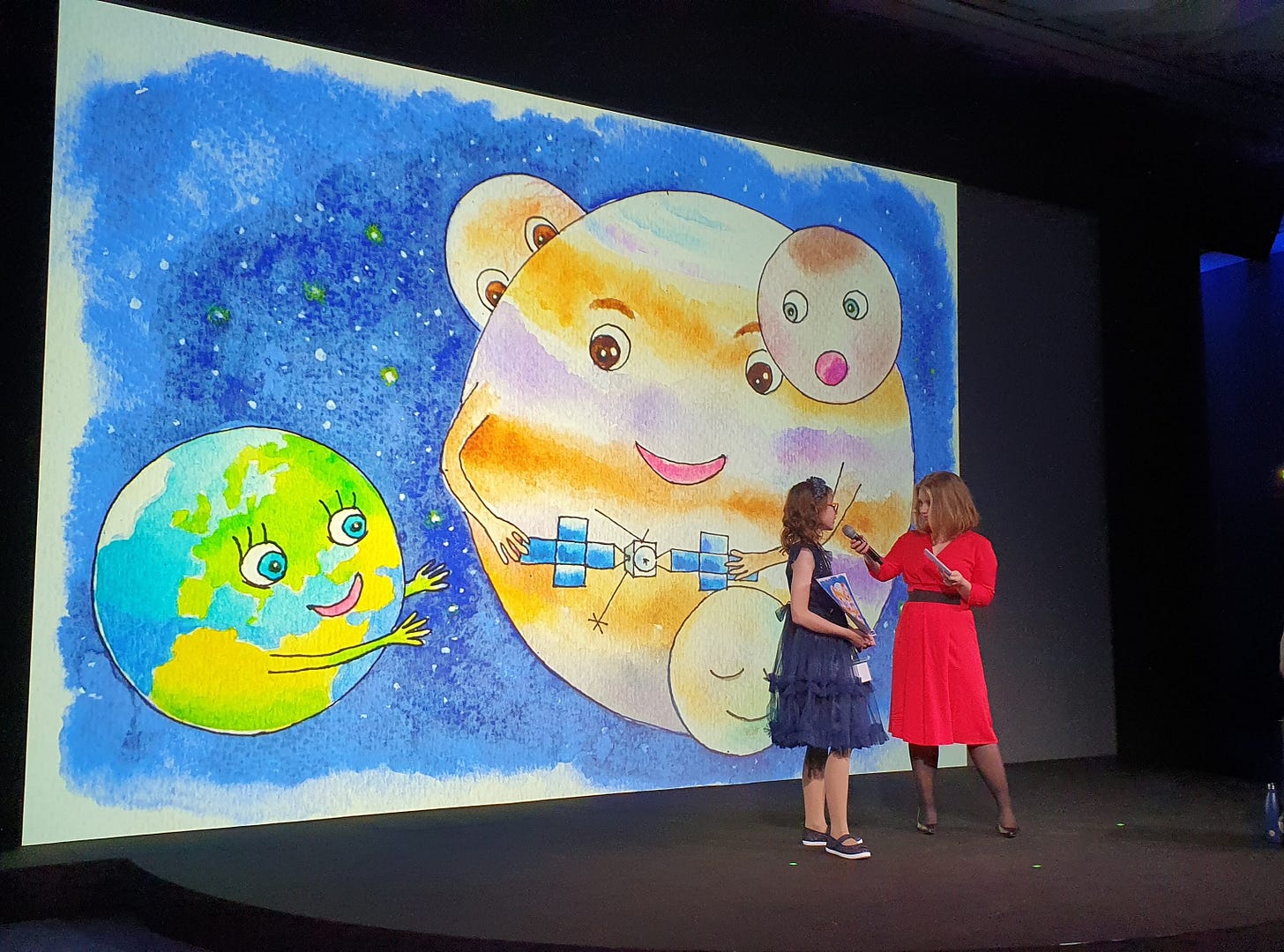

We had questions and schedules already planned out - I’d even had the chance to pick my favourite entry in the JUICE drawing competition, ready with an explanation for how I appreciated the blend of colours representing deep connectivity and coupling between Jupiter and its moons. I had interviews with the BBC all lined up, with a booth at the back of the auditorium, and an iPad perched precariously on a stack of wooden boxes ready for the live stream.

Alas, the best-laid plans rarely survive contact with reality.

The livestream from ArianeSpace, responsible for the launch activities in Kourou until the handoff to ESOC around 30 minutes after launch, showed grey skies above the launchpad. That’s not a problem in itself, but the weather plays an enormous role in launch timetables, with two main things to watch for: thunder clouds within ~10 km of the launch site producing a high risk of lightning; and high winds at any altitude above the launch site. I understand that launches will still happen into clouds and rain (frequent in tropical Kourou), so it’s not like they need clear skies for the launch. There’s a Go/No-Go decision made 10 minutes before launch that accounts for the changeable weather conditions.

The programme in the auditorium was glossy enough - short speeches from the great and the good; talk of the JUICE faring competition winner and the space cocktail that had been designed for JUICE. But 10 minutes before launch, we noticed some men in suits stand and leave the room in a hurry. Social media soon announced that the risk of lightning had scuppered Thursday’s launch, but it was some time before this was announced to the delegates at ESOC. When the news broke, both the livestream and the entire glossy programme ended abruptly.

I can appreciate the symmetry of lightning on Earth preventing the launch of a mission that can study lightning on Jupiter. But still.

Scrubbed

We were dazed, to put it mildly. The massive rush of adrenaline as launch approached, with all the green lights up to that point, had left us all on a high. This was really it! Fifteen years of work, and here we were at the final moments! Except they weren’t. And we now had to pick up the pieces.

The next couple of hours were chaotic. It was unclear how ESA would play the media strategy for the next launch attempt on Friday 14th, and whether the science team would be invited to stay for the press events (the press room was relatively small, so there are understandable priorities). TV live interviews were dropped, often moments before they were supposed to happen (I’ve learned not to take this personally). Plus many of us had to scramble to re-arrange flights, and book extra nights in hotels.

Social media remained the best way to follow what was happening, so we decamped from ESOC back to hotels, hoping for better news. The Plan B started to come together, and I went out for a much-needed Schwarzbier with colleagues.

Friday 14th: Take Two

Friday April 14th started with bright, spring sunshine in Darmstadt. Kourou woke to dramatic cloudy skies, and a weather radar showing isolated showers once again. The whisper machine started again: the forecast was awful; the forecast was fine. People were pessimistic; people were optimistic. The Ariane 5 uses cryogenic fuels, so hydrogen and oxygen in liquid form. According to the launch sequence on Spaceflight 101, the propellant loading begins 4hrs 50mins before launch (this is the “green/go for fuelling" marker), beginning with the first and second stages, then proceeding to the Vulcain main engine chilldown 3hrs 33mins before launch. A final propellant top-up occurs 2 hours before launch. In the event of a launch scrub, like we had on April 13th, the fuels are removed and fuelling has to be done again. But this all seemed to be taking place as planned on Friday morning, giving us cause for hope.

I tried and failed to get any work done all morning, then headed to ESOC with my colleagues at around 1pm, to sit in the press room for the launch. Several of the press team had stayed around for the second opportunity, including those from the “social space” group who had won places to be at ESOC for the launch, including Claire from the National Space Centre in Leicester.

It was simply wonderful to be in that room with colleagues, many of whom had been part of JUICE since its inception in 2007 or so. Olivier Witasse is the Project Scientist, leading the science team having taken over from Dima Titov (also with us at ESOC) a few years before. Michel Blanc, the original lead for the Laplace proposal, was there. Emma Bunce, my colleague from Leicester and member of the JMAG and UVS teams. And my fellow Interdisciplinary Scientist Olivier Grasset from Nantes, with whom I’ve shared a few long strolls along the Noordwijk beach at ESTEC. It was an immense privilege to share this moment with them, and vindicated my choice to travel to Germany rather than Kourou for the launch.

Friday’s press event was smaller, more relaxed, more friendly. We watched the live feed from ArianeSpace together, exchanging messages with colleagues in Kourou. Maybe after yesterday’s disappointment we tempered expectations - if it didn’t go on Friday, none of us would be in Darmstadt for the next opportunity on Sunday, and after that it was unclear when we could launch - the window would close in late April with sub-optimal conditions, and we didn’t wish to wait for the next launch opportunity in August.

But then, then… critical decision milestones came and went, the board remained green. The weather-related go/no-go decision ten minutes before launch, which had scuppered us on Thursday, came and went with smiles of relief on the livestream. Heart started racing as I literally perched on the edge of my seat with Emma, Olivier W and Olivier G, the clock ticking through L-5mins, L-3mins, L-1mins….

Time stopped and started. Hush at ESOC, no doubt hush across the launch sites in Kourou and the massive “Jupiter room” where the VIPs watch the launch.

The moment of truth, the Ariane 5 rocket sputtered to life at 12:14UTC. Was that flicker normal? Is it supposed to look like that? Should it take that long to rise beyond the tower? Is it rolling correctly? Doubts cascade through your mind, holding your breath, not daring to hope. Then that beautiful rocket is roaring skyward, the JUICE logo and artwork still visible atop a plume of fire and flame.

Exhalation, smiles, cheers - claps on the back, handshakes, relief that the moment has come and gone and there’s nothing that can turn us back now. More pessimistic colleagues reminding me that there are plenty of crucial milestones to come. They were right.

Signal Acquisition

We’re all on our feet now, too excited to sit still. We watch the livestream as the first and second stages are jettisoned, then after 27 minutes the spacecraft separates from the faring. Those minutes passed quickly, and we approached the time when ArianeSpace handed over to ESOC to manage the mission, waiting for the first acquisition of the signal to say that JUICE was healthy. By this time it was the large ground station in New Norcia, Australia, that was doing the listening, waiting expectantly for the signal acquisition.

But nothing. Silence. The spike of JUICE’s carrier signal was absent from the screens.

The elation and joy of launch was replaced by dread. Glancing around for reassurance, all I could see was frowns of concern. The ESA live stream went into a holding pattern, the hosts valiantly introducing the team members in the control room, with fake smiles that couldn’t hide the concern. WhatsApp messages from colleagues in Kourou suggesting that the mood had turned significantly in the room. Mumblings about spacecraft tumbling…

On one of the screens I spotted a colleague of ours, who had been helping to guide the mission from the beginning - instead of smiling for the cameras, he was staring at the screens, as if trying to compel JUICE to call home by sheer force of will alone. His face might have been carved from granite at that moment. Impending heartbreak.

They continued to fill time, a long interview with the folks at New Norcia that was hard to listen to. But then, what was that noise…? A faint sound of applause on the live stream? But nothing is being reported, they’re not breaking in with good news? Still a hush in the press room, then finally the stream cuts back to the REAL smiles, the overwhelming relief, and the dread turned to elation once again. There was that spike, that heartbeat from our spacecraft, reporting back to Earth.

It seems JUICE is determined to be a drama queen.

Now we’re told that the sequence is moving faster than expected, so solar panel deployment will come along long before ~2pm UTC when it was planned to happen. The livestream shows signals from the two wings, first one, then the other, with each enormous panel locking into place to form the 27-metre wide spacecraft in its final trajectory. We can see the trace of the power generation, at first negative, then shifting rapidly to positive as the spacecraft produces the electrical power it needs. Given the high sensitivity of the “low intensity” arrays needed for Jupiter, they’re pointed away from the Sun right now to prevent overheating.

We Have a Mission

With confirmation of solar panel deployment came the unbelievable news: we have a mission. We’re on our way to Jupiter.

Smiles, handshakes, and a satisfying feeling of European awkwardness in a moment of supreme happiness. No American hi-fives and hugs? No, that’s not what we do.

Trays suddenly appear with a smiling catering team, with something sparkling that tastes a bit like champagne. Clinks of glasses, a few photo opportunities, beaming smiles, but all rather understated. The most intense emotion for me was relief, particularly after the disappointment of Thursday, and the intense dread of waiting for signal acquisition. I tweeted, “wonderful, wonderful, wonderful” - I’m not sure I was capable of anything more articulate at that moment!

The following hours were a battle between happiness and exhaustion, as the adrenaline began to recede. I finally got my live BBC News Interview around 3pm BST. One by one, friends and colleagues departed. I was delighted to discover that a colleague from my school days was also at ESOC, working with the Mars Express team, and he kindly offered to take me on a tour - I got to see (through the windows) the main control room that had been talking to JUICE on the livestream, now a much calmer and relaxed environment. I saw inside the interplanetary spacecraft control room, where rows of multi-panel screens sit side by side, one per mission: this is where BepiColombo, Mars Express, Cluster and the like are operated from, commands uplinked and data downlinked, and monitored constantly by the dedicated staff at ESOC. Mars Express was on call at that very moment, but with uplink sequences in slight disarray due to the 24-hour delay of JUICE. After the first few days and weeks, JUICE operations will move to this room too. It was wonderful to see inside this nerve centre (thanks Simon!).

On Friday evening, a small crowd of us went for food and drinks to celebrate - it was low-key and friendly, I noticed a few stifled yawns, as many of us had not slept well, and had been on the go all day. It’s now Saturday, and I’m writing on the plane back to the UK, determined not to forget a thing about this incredible experience. It was a privilege to be at ESOC for the launch of JUICE, to share the moment with friends and colleagues. This really feels like a defining moment, the start of something exciting and new after years of planning. A near-perfect start to the mission, meaning that we don’t need to expend any unnecessary fuel to get us to Jupiter, leaving us with the fuel we need for our Jupiter tour and Ganymede mission.

To get to Jupiter, JUICE will now swing around the inner solar system for the next few years (as far out as the asteroid belt, as close in as Venus), gaining speed and energy from flybys of Earth and Venus, until the final slingshot out to Jupiter between 2029 and 2031. Instrument booms and antennae now need to deploy successfully, and we wait for the instruments to all be commissioned and cleared as healthy. We’ll see JUICE again when it flies by the Earth and Moon in August 2024. I think it’s fair to say that the next moment of dread and delight comes in 2031, when the main engine needs to fire to slow us down, allowing Jupiter’s immense gravity to grab ahold of our precious spacecraft.

But that’s all still to come. Word of the day: “all nominal”

Doesn’t really do it justice, does it???!